Small Colleges to Study Engineering: Why Size Isn’t a Disadvantage

Why Small Colleges to Study Engineering Are Often Overlooked

When families think about engineering education, they often picture large research universities—sprawling campuses, massive labs, and well-known brand names reinforced by rankings. The prevailing assumption is that real engineering happens at scale, where research output is high and graduate students fill the labs.

That assumption is understandable. Many outstanding engineering programs do exist at large universities, and rankings tend to reward research volume, funding, and institutional prestige. But environments built to advance cutting-edge research are not typically optimized for undergraduate learning.

In fact, some of the strongest undergraduate engineering experiences take place at small colleges purposefully designed around teaching, mentorship, and hands-on problem-solving. These programs often fly under the radar because they don’t match the mental model many families have of an engineering school.

For families interested in seeing concrete examples, I’ve compiled a list of underrated engineering colleges that deliver exceptional undergraduate outcomes beyond the rankings.

Small colleges are not the right choice for every aspiring engineer. But for the right student, they offer something increasingly rare in higher education: an engineering education built around undergraduates.

For a broader overview of how engineering programs differ structurally and how to approach the application process strategically, see our complete guide to engineering college admissions.

What We Mean by “Small Colleges to Study Engineering”

“Small colleges with engineering” are typically smaller institutions that offer one or more engineering academic programs and where undergraduate education is the central mission.

What unites these schools is not size alone, but intentional design. In small engineering programs, undergraduate students are the primary focus, and the academic environment is organized around their learning and development. Faculty teaching and advising are central to the program, with engineering courses taught directly by faculty members rather than through layered graduate instruction.

The distinctions between undergraduate-focused colleges and research universities are explored in more detail in University vs. College: What’s the Difference and How It Impacts the Student Experience.

Undergraduate-focussed programs foster engineering success.

Three Models of Small Engineering Colleges

Small colleges that offer engineering share an undergraduate focus but differ meaningfully in structure, scope, and student experience.

Understanding these distinctions helps families move toward a clearer sense of fit. Broadly, small engineering programs tend to fall into three models.

Standalone Engineering-Focused Colleges

These institutions are built almost entirely around engineering and applied science. Engineering is not one option among many — it is the core identity of the school.

Students in this model typically experience:

A fully immersive engineering environment from the first year

Highly project-based, collaborative curricula

Academic intensity that assumes strong interest and commitment to engineering

Examples include Olin College of Engineering, Rose‑Hulman Institute of Technology, and Harvey Mudd College. At the most specialized end of this model are institutions like Webb Institute, which focuses on a single engineering discipline.

This model tends to fit students who are confident in their interest in engineering and excited by depth, rigor, and total immersion. It is less well suited to students seeking exploration outside engineering or access to a wide range of non-technical majors.

As I’ve written in Illuminating Your Path to an Engineering Major and Career, understanding how clear a student’s engineering interests are is often the first step in determining which types of programs will be a strong fit.

This clarity also includes understanding which engineering disciplines may be a fit; for a deeper exploration, see our complete guide to choosing an engineering major.

Liberal Arts Colleges With Integrated Engineering

In this model, engineering exists within a broader liberal arts curriculum. Students study engineering alongside humanities, social sciences, writing, and the arts.

Common characteristics include:

Engineering programs intentionally integrated with liberal arts education

Strong emphasis on communication, ethics, and context

Flexibility for interdisciplinary study and intellectual exploration

A campus culture where engineers are part of a broader academic community

Examples include Swarthmore College, Smith College, Trinity College, and Union College.

This model often appeals to students who may want to study engineering but do not want to narrow their academic experience too quickly — particularly those interested in leadership, policy, design, or entrepreneurship.

For a look at a new related hybrid education model that blends technical expertise with humanistic depth see How Liberal Arts Engineering Degrees Prepare Students for an AI Future.

Teaching-Centered Small and Mid-Sized Institutions with Engineering

These institutions offer more scale and breadth than very small engineering colleges, without the size or research intensity of large R1 universities. They typically provide multiple engineering disciplines while maintaining a strong undergraduate focus.

Students in this model often encounter:

A broader range of engineering majors than at smaller colleges

Faculty engaged in research who also teach and advise undergraduates

Structured pathways to internships, co-ops, and industry partnerships

More campus resources than a small college, without the anonymity of a large R1 university.

Examples include Bucknell University, Lafayette College, Stevens Institute of Technology, and Clarkson University. Some of these institutions are formally colleges and others universities, but all share a similar undergraduate-focused engineering structure.

This model often works well for students who want applied learning and multiple engineering options — while still benefiting from smaller classes and closer faculty access than they would find at a large research university.

Because mechanical engineering is a widely offered engineering discipline at small colleges, it can be a useful lens for understanding how teaching models and student experience vary across institutions. For a closer look, see Best Colleges for Mechanical Engineering: How to Find the Right Fit Beyond the Rankings.

Computer engineering provides a similar lens, particularly at small and teaching-centered institutions where early systems work, hands-on labs, and close faculty mentorship shape how students learn to integrate hardware and software. See Best Colleges for Computer Engineering: How to Find the Right Fit Beyond the Rankings.

For families comparing engineering and computer science pathways, especially at small and teaching-centered institutions, our complete guide to computer science admissions explains how admissions expectations and program structures differ.

Smaller engineering programs can offer big advantages.

Why Small Engineering Colleges Excel at Undergraduate Engineering Education

Small engineering colleges are not scaled-down versions of large research universities. They are built around a different educational priority: undergraduate learning.

In many of these programs, engineering is not one department competing for institutional attention among many constituencies. It is a central academic mission. As a result, curriculum design, faculty roles, advising structures, and experiential learning are intentionally aligned around how undergraduates learn engineering best.

This does not mean small engineering colleges are “better” than large universities. It means they are optimized for a different purpose. For students whose primary goal is to develop strong foundational skills, confidence, and professional readiness as undergraduates, that distinction can matter enormously.

Several features consistently distinguish strong small engineering programs at the undergraduate level.

Faculty Whose Primary Role Is Teaching and Mentorship

At many small engineering colleges, faculty are hired, evaluated, and rewarded primarily for their work with undergraduates. Teaching, advising, and mentoring are central responsibilities.

As a result, undergraduate engineering students are more likely to:

Be taught by full-time faculty from the first year onward

Develop sustained relationships with professors across multiple courses

Receive direct faculty guidance on academic planning, projects, internships, and next steps

This matters in engineering, where learning is cumulative and conceptual gaps can compound quickly. When students struggle — or when they want to go deeper — access to faculty who know them well can make a meaningful difference in both learning and persistence.

Faculty mentorship also extends beyond the classroom. Professors frequently supervise undergraduate research and design projects, advise student teams, support internship searches, and write detailed recommendations grounded in long-term observation rather than brief classroom exposure.

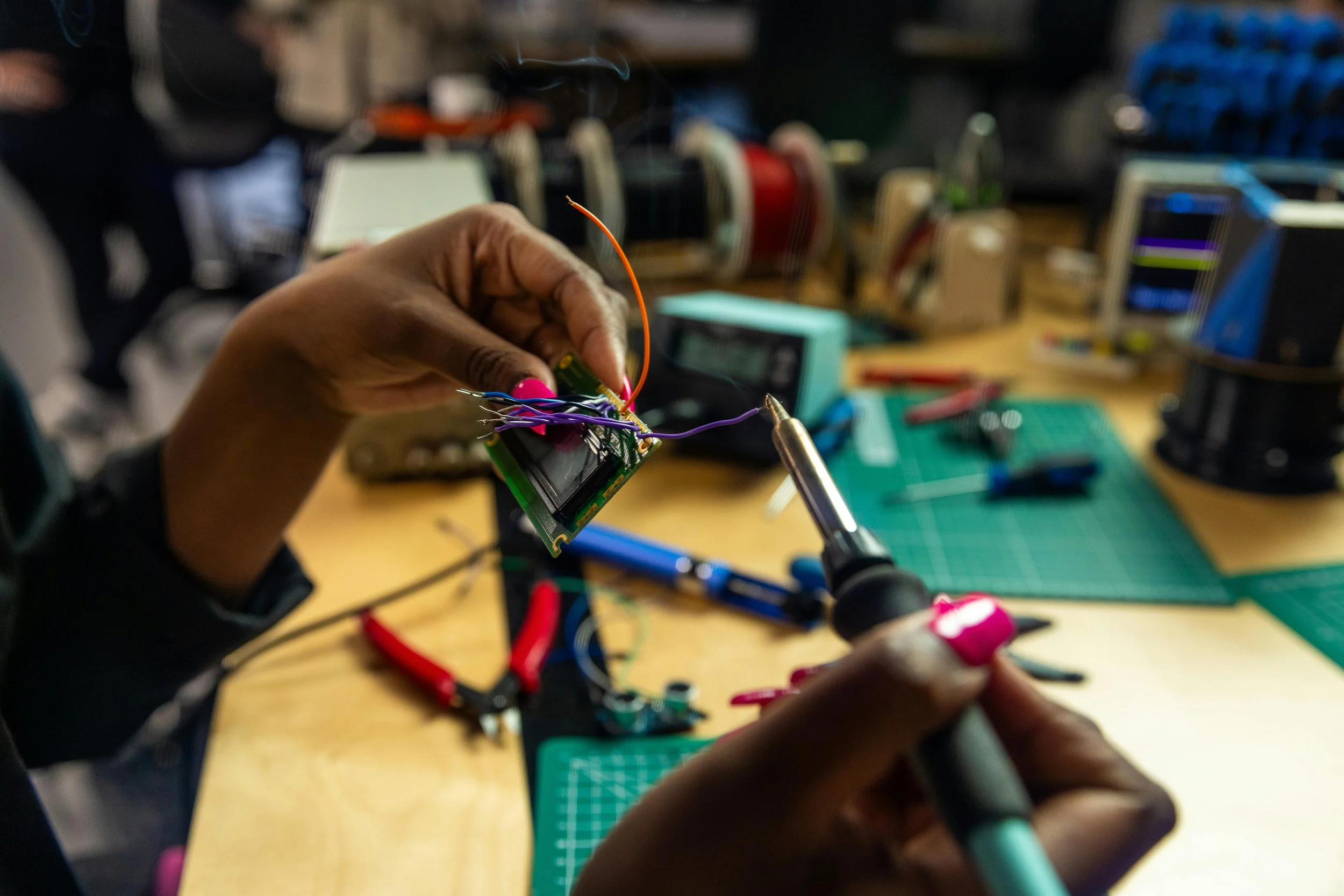

Earlier and More Meaningful Hands-On Engineering Work

One of the most consistent strengths of small engineering colleges is how early students engage in real engineering work.

Rather than spending the first two years primarily in large lecture-based math and science sequences, students at many small engineering programs:

Begin design- and project-based engineering courses in their first year

Build, test, and iterate as part of required coursework

Work in undergraduate-focused labs and maker spaces throughout the curriculum

This early exposure helps students connect theory to practice sooner. They learn how engineering concepts function in real systems, how to work through design constraints, and how to respond productively when projects fail — which they inevitably do.

Hands-on learning also plays a critical role in confidence-building. Students who begin doing engineering from the start are more likely to develop a clear sense of themselves as engineers — a factor that supports persistence — rather than feeling like they are waiting years for “real” engineering to begin.

A Cohesive Engineering Identity

At large universities, engineering students are often one subgroup among many thousands of undergraduates. At small engineering colleges, undergraduate engineers are the primary focus.

Engineering cohorts tend to be tight-knit, collaborative, and academically engaged, with shared expectations around workload and commitment. Expectations are clear, help is accessible, and students are known not just as names on a roster, but as developing engineers.

Preparation for Industry, Co-ops, and Applied Careers

Small engineering colleges are sometimes assumed to be less connected to industry than large universities. In practice, many produce graduates who are exceptionally well prepared for engineering careers after graduation.

Several factors contribute to this:

Curricula emphasize problem-solving, teamwork, and communication alongside technical depth

Faculty often bring industry experience into teaching and project supervision

Career advising tends to be individualized rather than transactional

At some institutions, such as Olin College of Engineering, students regularly work on industry-connected design projects that mirror real engineering constraints and expectations.

Many small engineering colleges also maintain strong pipelines to internships, co-ops, and industry partners, helping students move from undergraduate work to professional engineering roles with confidence.

Engineering success starts with finding the right learning environment.

How to Choose a Small College to Study Engineering Using a Deep-Fit™ Lens

Choosing a small college to study engineering is about identifying an environment where a particular student will thrive.

Our Deep-Fit™ admissions approach shifts the question from Is this a strong engineering program? to Is this program built in a way that supports how this student learns, works, and grows?

The questions below help families evaluate that fit more clearly.

Who Teaches Undergraduates — and When?

One of the most important — and often overlooked — questions in engineering education is who is actually teaching undergraduates, especially in the first two years.

At some institutions, introductory engineering, math, and science courses are taught primarily by full-time faculty who also advise students and supervise projects. At others, these courses may be taught largely by graduate students, temporary instructors, or even undergraduate teaching assistants.

Families should ask:

Who teaches first-year and sophomore engineering courses?

Is there a culture of faculty mentorship, not just instruction?

How are faculty evaluated and rewarded for undergraduate teaching?

How accessible are faculty outside of class?

In small engineering programs, undergraduates are more likely to be taught by experienced faculty who know the curriculum well, follow students’ progress over time, and take responsibility for both instruction and advising. That continuity can shape everything from academic confidence to research, internships, and recommendations.

How Early and Often Do Students Engage in Real Engineering Work?

Not all engineering programs introduce engineering in the same way.

Some expect students to spend their early years primarily completing prerequisite math and science coursework, with limited exposure to engineering design until later. Others integrate engineering work throughout the undergraduate experience, beginning in the first year.

Key questions include:

Is there a required first-year engineering curriculum that introduces how engineers think and work?

Do students engage in design- or project-based engineering in the first year?

Is hands-on engineering work required or optional?

Are labs, studios, or maker spaces central to both the curriculum and the engineering culture?

What role do undergraduates play in research or faculty-led projects?

Is there a required senior capstone or culminating engineering design project that integrates learning across the curriculum?

Early and sustained engagement matters. Students who begin doing engineering sooner tend to connect theory to practice more effectively, develop confidence earlier, and persist more readily through the inevitable challenges of the major.

For students who are still exploring whether engineering is the right path, flexibility and early exposure can be especially important; see Navigating the College Search for the Undecided STEM Student for additional guidance.

What Does Advising Actually Look Like for Engineering Students?

“Strong advising” is a phrase used by nearly every institution — but it can mean very different things in practice.

Families should look into:

Is there a required first-year advising seminar or structured first-year curriculum that supports academic planning and adjustment?

Is advising faculty-led or centralized through professional staff? If a hybrid model, what roles does each play?

How often do engineering students meet with advisors?

Who helps students plan coursework, internships, research, or study abroad?

How are students supported if they struggle or reconsider their path?

In smaller engineering programs, advising is often more proactive and integrated into the academic experience. Advisors tend to know students well and can help them navigate not just requirements, but decisions about focus, pacing, and opportunities.

How Are Internships, Co-ops, and Outcomes Supported?

Outcomes matter — but families should look beyond headline statistics to understand how outcomes are supported.

Useful questions include:

Are internships, co-ops, or other structured work experiences available to engineering students?

If so, how does the program support students in securing and succeeding in them?

Are there structured partnerships with industry?

What kinds of roles do graduates pursue after college?

Families may also want to consider whether a program’s ABET accreditation aligns with a student’s academic and professional goals.

How visible and accessible is career support for engineering students?

How does the institution intentionally support professional readiness (for example, through first-year courses, seminars, or required career preparation curricula)?

At many small engineering colleges, career advising is personalized, not transactional. Faculty and advisors often play an active role in connecting students to opportunities and helping them prepare for next steps.

Does the Engineering Culture Match the Student?

Finally, fit is cultural as well as academic.

Even among small engineering programs, cultures vary widely. Some are highly immersive and intense; others intentionally balance engineering with broader exploration. Some emphasize collaboration; others are more competitive.

Families should ask:

Is the environment collaborative or competitive?

How intense is the workload — and how is that intensity supported?

Do students feel known and supported by faculty and peers?

How do students describe their day-to-day academic experience?

A program can be academically strong and still be the wrong fit. The goal is to find the program where a student can thrive — academically, personally, and as a developing engineer.

Strong engineering outcomes are built through teaching, mentorship, and hands-on learning.

Small Colleges: A Powerful Path to Engineering Success

When families think about engineering education, it’s easy to default to size, rankings, or research prominence as proxies for quality. But undergraduate engineering success is shaped far more by how students are taught, supported, and engaged.

Small colleges that offer engineering degrees provide a fundamentally different undergraduate experience—one built around strong teaching, mentorship, and early hands-on learning, all of which can be harder to find at larger universities.

A thoughtful college search is not about chasing prestige or rankings, but about identifying where a student is most likely to thrive. For many aspiring engineers, small colleges represent a powerful—and often underestimated—path to engineering success.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are small colleges good for engineering majors?

Yes — for the right student. Many small colleges offer ABET-accredited engineering programs with strong undergraduate teaching, early hands-on design work, and close faculty mentorship. Students who value access to professors and a cohesive academic community often thrive in these environments.

Will attending a small engineering college limit job opportunities?

No. Many small engineering colleges maintain strong industry connections, co-op pipelines, and internship support. Outcomes depend more on preparation, engagement, and program structure than institutional size alone.

Do small colleges offer ABET-accredited engineering degrees?

Many do. Families should confirm accreditation for specific majors if professional licensure is a goal. ABET accreditation is particularly relevant in disciplines such as civil, mechanical, and electrical engineering.